Last week I got to spend three days on Florida’s Atlantic coast with five of my college roommates (missed you, Bria and Karen!). Twenty-five years after graduating, I was feeling the profound blessing of history with those women. We caught up on life, families, kids, work, lessons learned and lessons-in-process, and the hopes that even with all the blessings each of us can recount from the past twenty-five years, the best of The Rest of Our Stories is still to come.

Flagler Beach is among my favorite Florida beaches! It was my first time to visit, and I’d return in a heartbeat. Not too touristy or busy, with quaint shops and eateries. I love fish tacos and am now convinced that Mahi Mahi tastes even better a hundred yards from the rolling tide.

Life has a way of seasoning all of us. Combined, we’ve dealt with losses of loved ones, marriage, health, home, jobs, hearts, and hope. And we’ve been blessed abundantly too. We laughed, reminisced, cried, hoped anew, boosted each other’s faith, shared new perspectives, got silly, got sun, and lived a few more days of good life together.

I also got a chance to see some ruins and take note of the stories they left behind. History has much to teach us in the present, which is part of the heart of The Rest of the Story. Our stories are richer and deeper because of those that others leave behind–if we train ourselves to pause and take note.

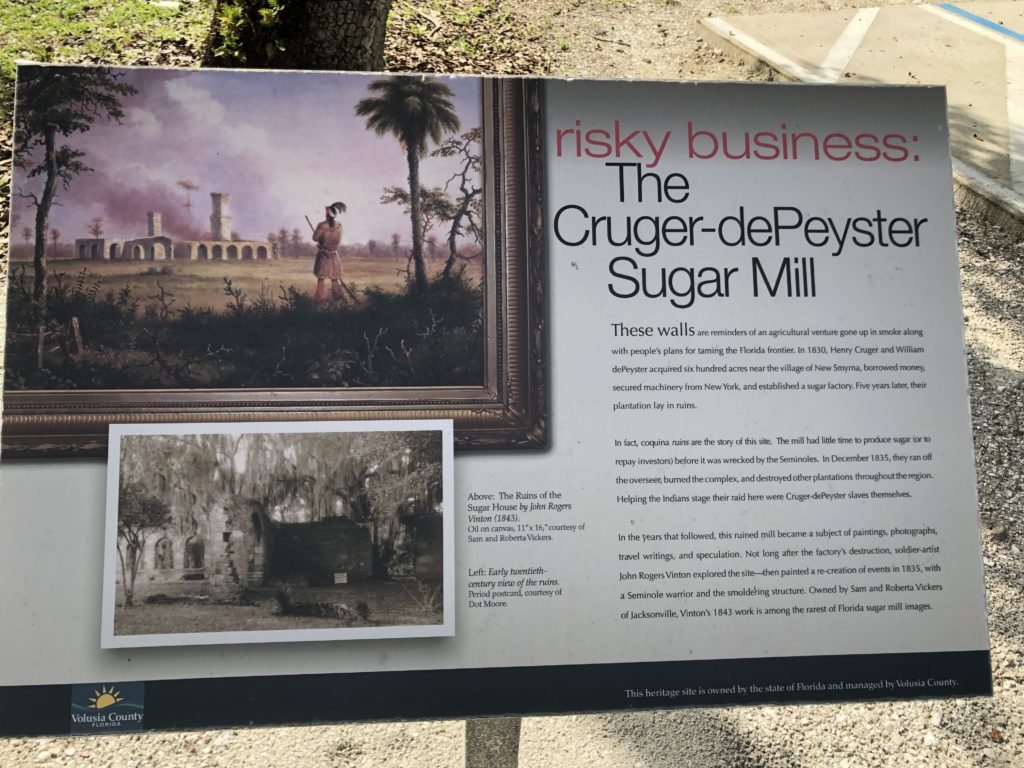

At the beginning of the trip, I visited the ruins of the Cruger-dePeyster Sugar Mill in New Smyrna. In August 1970, it was added to the US Register of Historic Places. I didn’t know until returning to Arkansas for more research that this mostly unknown place shares a connection to the Hudson Valley , a region of our country that I’m focusing on and posting about while working on my current novel. The machinery at this mill came from the West Point Foundry in Cold Spring, New York.

William DePeyster and Henry Cruger were merchant speculators from New York who built the sugarcane mill and sawmill on seventeen acres near New Smyrna. Eliza Cruger, Henry’s wife, along with other investors, financed construction on the land that Cruger purchased from an Episcopal minister, who received it as a grant from the Spanish crown. Somehow along the way, the original grant was to Andrew Turnbull by the British during their 22-year occupation of Florida.

The masonry buildings included the sugarcane mill and sawmill. These were built from coquina, a sedimentary rock of fossilized mollusk shells. The crushing house, shown in the above photos, included a chimney and arched doors and windows. It held the steam-driven grinding machinery that extracted the juice from the sugarcane. All of this work relied on slave labor and draft animals.

I didn’t read records of any of the slaves’ names, but as with the other plantations I’ve visited, being among the shadows and memories of ruins such as these drew respect for the individual people who toiled in these now-crumbling structures.

On Christmas day, 1835, the mill was pillaged and burned in a battle between the Seminoles and the United States.

Old ruins may not seem to serve much purpose other than remind us of what was. But then again, without the lessons of what was, we lose an important measure of wisdom for what is and is to come. I think that’s why they fascinate me. The people who lived among what now are ruins finished their lives. Mine is not over yet. Those two truths keep nudging me to make the most of The Rest of My Story.